A classic Rolleiflex with a

modern meter (2013)

This

is an old dream, a classic Rolleiflex with a

modern meter. Admittedly, there is not much wrong with the original

meter, as long as it works. But the meter takes its signal from a selenium cell, and

most of

these have meanwhile given to work properly. Typically, the element

characteristics change in a way that they indicate too low at higher light

levels,

so that (if you stick to the meter) exposure may still be correct at

lower

light levels, but the pictures will come out overexposed when it is

bright.

Technically, this is down to

the sealing of the

selenium cells by some kind of laquer, that starts to fail and that

lets the

performance of the cell degrade. Contrary to what you can read

sometimes, the

reason is not the amount of light that the cells had to absorb over

time. A

Selenium meter can lie in the sun for decades, with the needle at max

as long

as the cell is “tight”, this will not do harm.

After

the end of serial production, Rollei and the

meter manufacturer have supplied spare parts for a couple of years, but

when

this ended, there was indeed a kind of run for the few selenium cells

that were

still available, and without which the meters of the classic and much

loved

Rolleiflex cameras just didn’t work. I remember that I spoke

to a person from

Gossen (at around 1995) who admitted that they were constantly getting

inquiries from serious Rollei users, whom they would love to help, but

whom

they were – since they had abandoned (and scrapped) the

entire selenium

technology – just unable

to help.

And

even if one had finally got hold of a working

(old) selenium cell, this could itself become bad a week later. On the

very

camera that this chapter is about, I had the cell replaced with a

new one

– a repair that lasted for about six months….

This

is now all water under the bridge. Every now and

then, new (old) selenium cells turn up on Ebay, sold “as

is”, for still

significant money. And the remaining lovers of the late Rollei TLRs now

use a

hand held meter – of have bought a GX.

Which

is a pity, because the iconic Rollei TLR is

characterised by this row of humps in front of the meter cell, over

which I ran

my fingers when I was a child. Also, the handling of the

“F” is unsurpassed,

this is ergonomics at its best. The GX is a fine camera, but only

second best,

and when I see a F with a handheld meter, I feel sad.

Well,

after my own 3,5F was back to a “laggy” meter

again, and I couldn’t bring myself to investing into yet

another new cell, I

remembered a discussion in the “RUG”, the Rollei User

Group, that circled around

the possibility to replace the selenium thing with some more modern

technology,

but that led nowhere, and the project disappeared in some drawer for

around 15

years.

Until

I just recently read somebody’s report on the

internet, who claimed to have replaced the selenium cell (of a Russian

Zenit)

with the solar cell of an old calculator. I had an old calculator and

indeed

the needle moved – however far from the correct amount.

Still

the idea was back on my mind, and I also got the

nevessary help in my

favourite photo forum.

Thanks

a lot Jürgen, for your guidance to stop messing

with solar cells, and for your patience and your help. Without you,

this

project would not have been completed.

As

said, the idea was to replace the original selenium

cell with a modern photo diode (BPW21) and to operate the camera

instrument

with it, via suitable electronics, so that the match-needle metering

concept of

the camera remained intact and the camera itself stayed unchanged, at

last

optically. Aside from the diode, the camera would have to house the

electronics

board somewhere, together with a battery and a switch to start the

meter (and

some cables).

The

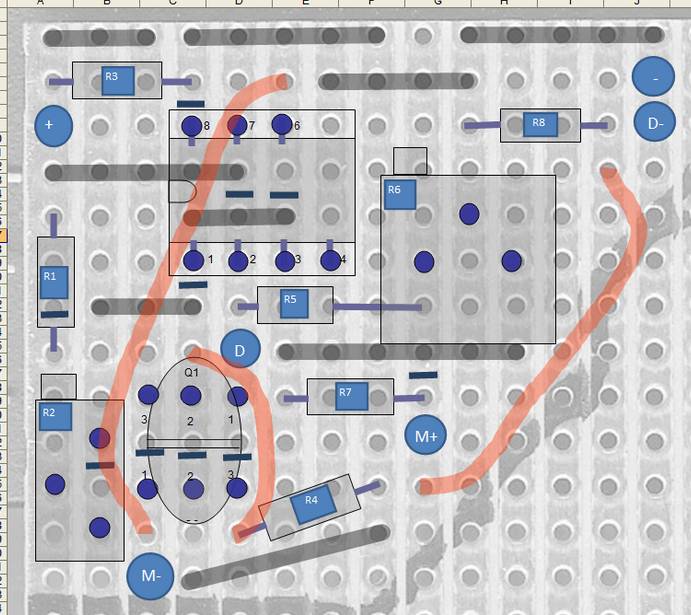

electronic circuitry is from the data sheet of the

IC LM10, but not exactly. To enable a full scale deflection of the

instrument,

some resistor values had to be changed.

The

board layout nearly drove me crazy. My first tries

needed multiple additional wires, the last version only needs three:

Before

version 1.0, which now sits in the camera,

I had to make four prototypes. Number one did work, but was unable to

produce

that full scale deflection, and was much too high for the space I had

planned

to fit it in. Number two and three did not work at all, for whatever

reason.

Number four worked well, but was still too high, so that the focusing

screen

image was obscured a little.

I

learned a lot about soldering…

Selecting

transistors was a funny exercise. I had to

do this after I had ruined the (expensive) LM394

“supermatch” pair of

transistors. Two transistors of identical amplification had to be

selected,

glued together and fitted under a common cork

“cap”.

Now,

the electronics sit in the mirror box, in the

space kindly provided by Franke & Heidecke, to the right of the

reflex

mirror, the battery to the left below the lever that actuates the

parallax

mask.

The

numerous cables are all under the mirror – and I

hope they stay there.

The

photo diode is where the selenium cell used to be,

if one looks closely it can be spotted there, this could not be

avoided.

This

left me with the problem of how to switch the

meter on. Other than the selenium cell, which lives on sunshine

alone,

electronics need a battery and also a switch (or rather a push button

thing,

because on/off switches are so easily forgotten).

Unfortunately,

the circuitry does not lend itself to

fit a timer that would keep the meter on for a couple of seconds, after

switched on once. On the other hand, the classic way of handling a

Rolleiflex

is with both hands, where the camera rests in the hands and aperture

and speed

are adjusted with the thumbs, and where the index fingers are free to

e.g. operate

a meter switch.

Quite comfortable, even if it does not look so on this

picture.

I

eventually decided against the initial idea to

somehow switch the meter on via the shutter release button. For once,

there is

not much space to easily fit a switch, and I was also reluctant to make

the

butter smooth shutter release any harder to press. This soft shutter is

one

contributor to the fact that shutter speeds as slow as 1/15 can often

be used

hand-held on a Rolleiflex. And (at least on my camera) I am sure I

would have

often released the shutter accidentally, when all I wanted was to

activate the

meter.

So

I sacrificed the P/C (flash) socket. This is a

sacrilege for sure and it does permanently modify the camera (something

I had

said I would avoid). On the other hand I will not use the camera with a

flash

(I don’t like flash photography anyway) and this is a perfect

place for a button.

Where the P/C socket once was, the left index finger starts the meter,

the

thumbs adjust speed and apertuire to match the needle, and the right

index

finger stays free to wait for that decisive moment.

So

the final camera is almost

unchanged from the outside. The meter works well, as if it

was never out of order. To adjust the meter to the correct exposure was

a piece

of cake, eventually, and – all in all – I do not

feel I have ruined that

classic camera at all. Had Rollei stayed in the business after 1981,

they might

have done something similar, they already had prototypes (to be found

in

Prochnow’s books)

One

word of caution, should somebody now plan to also

do this modification, after being fed up with the lame meter of his

beloved

“F”. As much as I am delighted if somebody draws

inspiration from my tinkering,

this particular one wasn’t simple, even if it now looks so

inconspicuous. I am

happy to help, but this is not a “plug and Play”

solution…

(to top)